Church Art Bird Carrying Body Through the Clouds to Heaven

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, oil on oak panels, 205.5 cm × 384.ix cm (81 in × 152 in), Museo del Prado, Madrid

The Garden of Earthly Delights is the modern title[a] given to a triptych oil painting on oak panel painted by the Early Netherlandish master Hieronymus Bosch, betwixt 1490 and 1510, when Bosch was between 40 and sixty years quondam.[1] It has been housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Espana since 1939.

As picayune is known of Bosch'south life or intentions, interpretations of his intent range from an admonition of worldly fleshy indulgence, to a dire alarm on the perils of life's temptations, to an evocation of ultimate sexual joy. The intricacy of its symbolism, specially that of the central panel, has led to a wide range of scholarly interpretations over the centuries. Twentieth-century art historians are divided as to whether the triptych'due south central console is a moral warning or a panorama of paradise lost.

Bosch painted iii large triptychs (the others are The Last Judgment of c. 1482 and The Haywain Triptych of c. 1516) that tin can exist read from left to correct and in which each panel was essential to the significant of the whole. Each of these iii works presents distinct nevertheless linked themes addressing history and faith. Triptychs from this period were generally intended to be read sequentially, the left and right panels often portraying Eden and the Terminal Judgment respectively, while the main subject was contained in the center piece.[two] It is not known whether The Garden was intended as an altarpiece, but the general view is that the extreme discipline matter of the inner center and correct panels brand information technology unlikely that it was intended to function in a church building or monastery, but was instead commissioned by a lay patron.[3]

Clarification [edit]

Exterior [edit]

The outside panels evidence the world during cosmos, probably on the Third Twenty-four hours, after the addition of plant life but before the appearance of animals and humans.[4]

When the triptych's wings are airtight, the design of the outer panels becomes visible. Rendered in a light-green–grey grisaille,[5] these panels lack colour, probably because most Netherlandish triptychs were thus painted, but possibly indicating that the painting reflects a time before the creation of the dominicus and moon, which were formed, according to Christian theology, to "requite light to the earth".[6] The typical grisaille blandness of Netherlandish altarpieces served to highlight the splendid colour within.[7]

The outer panels are generally thought to depict the cosmos of the world,[viii] showing greenery beginning to clothe the yet-pristine Earth.[9] God, wearing a crown like to a papal tiara (a common convention in Netherlandish painting),[6] is visible equally a tiny effigy at the upper left. Bosch shows God as the male parent sitting with a Bible on his lap, creating the Earth in a passive way by divine fiat.[10] Above him is inscribed a quote from Psalm 33 reading "Ipse dīxit, et facta sunt: ipse mandāvit, et creāta sunt"—For he spake and it was done; he commanded, and it stood fast.[11] The Earth is encapsulated in a transparent sphere recalling the traditional depiction of the created world as a crystal sphere held by God or Christ.[12] It hangs suspended in the cosmos, which is shown as an impermeable darkness, whose only other inhabitant is God himself.[vi]

Despite the presence of vegetation, the world does not all the same comprise man or brute life, indicating that the scene represents the events of the biblical Third Day.[4] Bosch renders the institute life in an unusual fashion, using uniformly grayness tints which brand it difficult to determine whether the subjects are purely vegetable or perhaps include some mineral formations.[4] Surrounding the interior of the globe is the sea, partially illuminated past beams of light shining through clouds. The exterior wings have a clear position within the sequential narrative of the work equally a whole. They prove an unpopulated earth composed solely of rock and plants, contrasting sharply with the inner central panel which contains a paradise teeming with lustful humanity.

Interior [edit]

Left panel

Center console

Right panel

Scholars take proposed that Bosch used the outer panels to establish a Biblical setting for the inner elements of the work,[5] and the exterior epitome is mostly interpreted as prepare in an before time than those in the interior. Every bit with Bosch's Haywain Triptych, the inner centerpiece is flanked by heavenly and hellish imagery. The scenes depicted in the triptych are thought to follow a chronological social club: flowing from left-to-right they represent Eden, the garden of earthly delights, and Hell.[13] God appears as the creator of humanity in the left hand wing, while the consequences of humanity's failure to follow his volition are shown in the right.

Naked figures seek pleasure in various ways. Middle panel, women with peacock (detail)

Yet, in contrast to Bosch's two other complete triptychs, The Concluding Judgment (effectually 1482) and The Haywain (after 1510), God is absent from the primal console. Instead, this panel shows humanity acting with apparent free will every bit naked men and women engage in various pleasure-seeking activities. According to some interpretations, the correct hand panel is believed to show God'due south penalties in a hellscape.[14]

Art historian Charles de Tolnay believed that, through the seductive gaze of Adam, the left panel already shows God'southward waning influence upon the newly created earth. This view is reinforced by the rendering of God in the outer panels equally a tiny figure in comparison to the immensity of the earth.[xiii] According to Hans Belting, the three inner panels seek to broadly convey the Quondam Testament notion that, before the Fall, there was no defined boundary between practiced and evil; humanity in its innocence was unaware of consequence.[15]

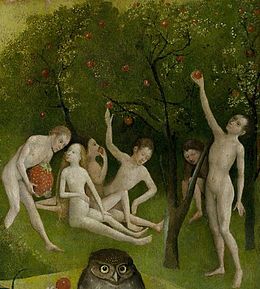

Left panel [edit]

The left panel (sometimes known every bit the Joining of Adam and Eve)[17] depicts a scene from the paradise of the Garden of Eden commonly interpreted as the moment when God presents Eve to Adam. The painting shows Adam waking from a deep sleep to discover God holding Eve by her wrist and giving the sign of his approval to their wedlock. God is younger-looking than on the outer panels, blueish-eyed and with gilt curls. His youthful appearance may be a device past the artist to illustrate the concept of Christ as the incarnation of the Word of God.[eighteen] God's correct hand is raised in approval, while he holds Eve's wrist with his left. According to the work's well-nigh controversial interpreter, the 20th-century folklorist and art historian Wilhelm Fraenger:

Equally though enjoying the pulsation of the living blood and as though as well he were setting a seal on the eternal and immutable communion between this human blood and his own. This concrete contact between the Creator and Eve is repeated even more noticeably in the fashion Adam's toes bear upon the Lord's foot. Here is the stressing of a rapport: Adam seems indeed to be stretching to his full length in order to make contact with the Creator. And the billowing out of the cloak around the Creator's middle, from where the garment falls in marked folds and contours to Adam's anxiety, besides seems to indicate that hither a electric current of divine power flows downwards, and then that this group of three really forms a closed excursion, a complex of magical energy ...[19]

Eve avoids Adam's gaze, although, according to Walter S. Gibson, she is shown "seductively presenting her body to Adam".[20] Adam's expression is one of anaesthesia, and Fraenger has identified three elements to his seeming astonishment. Firstly, at that place is surprise at the presence of the God. Secondly, he is reacting to an awareness that Eve is of the same nature as himself, and has been created from his own body. Finally, from the intensity of Adam'southward gaze, information technology can be ended that he is experiencing sexual arousal and the primal urge to reproduce for the first time.[21]

Birds swarming through cavities of a hut-shaped form in the left background of the left console

The surrounding landscape is populated by hut-shaped forms, some of which are made from stone, while others are at least partially organic. Backside Eve rabbits, symbolising fecundity, play in the grass, and a dragon tree reverse is thought to represent eternal life.[20] The background reveals several animals that would have been exotic to contemporaneous Europeans, including a giraffe, a monkey riding an elephant, and a lion that has killed and is virtually to devour his prey. In the foreground, from a big hole in the ground, emerge birds and winged animals, some of which are realistic, some fantastic. Behind a fish, a person clothed in a short-sleeved hooded jacket and with a duck'southward beak holds an open book as if reading. To the left of the area a cat holds a pocket-sized lizard-similar creature in its jaws. Belting observes that, despite the fact that the creatures in the foreground are fantastical imaginings, many of the animals in the mid and background are drawn from gimmicky travel literature, and here Bosch is appealing to "the knowledge of a humanistic and aristocratic readership".[22] Erhard Reuwich's pictures for Bernhard von Breydenbach's 1486 Pilgrimages to the Holy Land were long idea to be the source for both the elephant and the giraffe, though more recent research indicates the mid-15th-century humanist scholar Cyriac of Ancona's travelogues served as Bosch's exposure to these exotic animals.[22]

According to art historian Virginia Tuttle, the scene is "highly unconventional [and] cannot be identified as whatsoever of the events from the Book of Genesis traditionally depicted in Western art".[23] Some of the images contradict the innocence expected in the Garden of Eden. Tuttle and other critics have interpreted the gaze of Adam upon his wife equally lustful, and indicative of the Christian belief that humanity was doomed from the showtime.[23] Gibson believes that Adam'southward facial expression betrays not just surprise but also expectation. According to a conventionalities mutual in the Middle Ages, before the Fall Adam and Eve would have copulated without lust, solely to reproduce. Many believed that the offset sin committed later on Eve tasted the forbidden fruit was lecherous lust.[24] On a tree to the right a snake curls effectually a tree trunk, while to its right a mouse creeps; according to Fraenger, both animals are universal phallic symbols.[25]

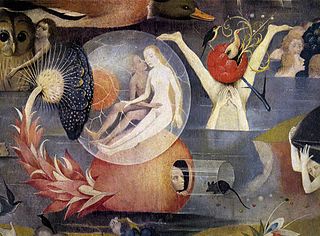

Center panel [edit]

The central water-bound globe in the center panel's upper groundwork is a hybrid of stone and organic affair. It is adorned past nude figures cavorting both with each other and with various creatures, some of whom are realistic, others are fantastic or hybrid.

The skyline of the center panel (220 × 195 cm, 87 × 77 in) matches exactly with that of the left fly, while the positioning of its cardinal puddle and the lake backside it echoes the lake in the earlier scene. The center image depicts the expansive "garden" landscape which gives the triptych its name. The panel shares a mutual horizon with the left wing, suggesting a spatial connectedness between the two scenes.[26] The garden is teeming with male person and female nudes, together with a variety of animals, plants and fruit.[27] The setting is not the paradise shown in the left console, just neither is it based in the terrestrial realm.[28] Fantastic creatures mingle with the real; otherwise ordinary fruits appear engorged to a gigantic size. The figures are engaged in diverse amorous sports and activities, both in couples and in groups. Gibson describes them as behaving "overtly and without shame",[29] while fine art historian Laurinda Dixon writes that the human figures showroom "a certain boyish sexual marvel".[17]

Many of the numerous human figures revel in an innocent, cocky-absorbed joy as they engage in a wide range of activities; some announced to enjoy sensory pleasures, others play unselfconsciously in the water, and yet others cavort in meadows with a multifariousness of animals, seemingly at one with nature. In the middle of the background, a large blue globe resembling a fruit pod rises in the eye of a lake. Visible through its circular window is a human holding his correct hand shut to his partner's genitals, and the blank buttocks of yet another figure hover in the vicinity. According to Fraenger, the eroticism of the center frame could be considered either as an apologue of spiritual transition or a playground of corruption.[xxx]

A grouping of nude females from the center panel. The head of one female is adorned with two cherries—a symbol of pride. To her right, a male drinks lustfully from an organic vessel. Behind the group, a male carries a couple encased in a mussel shell.[31]

On the right-hand side of the foreground stand a group of four figures, three white- and ane blackness-skinned. The white-skinned figures, two males and ane female, are covered from head to foot in light-chocolate-brown trunk hair. Scholars generally concord that these hirsute figures stand for wild or primeval humanity, merely disagree on the symbolism of their inclusion. Fine art historian Patrik Reuterswärd, for case, posits that they may be seen as "the noble savage" who represents "an imagined alternative to our civilized life", imbuing the panel with "a more articulate-cut primitivistic note".[32] Writer Peter Glum, in contrast, sees the figures as intrinsically connected with whoredom and lust.[33]

In a cave to their lower right, a male effigy points towards a reclining female who is also covered in hair. The pointing human is the only clothed effigy in the console, and as Fraenger observes, "he is clothed with emphatic thrift right upwardly to his throat".[34] In addition, he is one of the few human figures with dark hair. According to Fraenger:

The fashion this human's dark hair grows, with the sharp dip in the heart of his high brow, as though concentrating there all the energy of the masculine Thou, makes his face different from all the others. His coal-black eyes are rigidly focused in a gaze that expresses compelling force. The nose is unusually long and boldly curved. The mouth is wide and sensual, but the lips are firmly close in a straight line, the corners strongly marked and tightened into terminal points, and this strengthens the impression—already suggested by the eyes—of a strong decision-making will. It is an extraordinarily fascinating confront, reminding us of faces of famous men, especially of Machiavelli's; and indeed the whole aspect of the head suggests something Mediterranean, as though this man had acquired his frank, searching, superior air at Italian academies.[34]

A grouping of figures pluck fruit from a tree. A human carries a large strawberry, while an owl is in the foreground.

The pointing homo has variously been described as either the patron of the work (Fraenger in 1947), equally an advocate of Adam denouncing Eve (Dirk Bax in 1956), as Saint John the Baptist in his camel'south skin (Isabel Mateo Goméz in 1963),[35] or equally a cocky-portrait.[fifteen] The woman below him lies inside a semicylindrical transparent shield, while her rima oris is sealed, devices implying that she bears a secret. To their left, a man crowned by leaves lies on summit of what appears to be an actual but gigantic strawberry, and is joined by a male and female person who contemplate some other as huge strawberry.[35]

There is no perspectival social club in the foreground; instead it comprises a series of small motifs wherein proportion and terrestrial logic are abandoned. Bosch presents the viewer with gigantic ducks playing with tiny humans nether the cover of oversized fruit; fish walking on land while birds dwell in the water; a passionate couple encased in an amniotic fluid bubble; and a man inside of a red fruit staring at a mouse in a transparent cylinder.[36]

The pools in the fore and background contain bathers of both sexes. In the key round pool, the sexes are mostly segregated, with several females adorned by peacocks and fruit.[31] Four women acquit cherry-like fruits on their heads, mayhap a symbol of pride at the fourth dimension, equally has been deduced from the contemporaneous saying: "Don't eat cherries with great lords—they'll throw the pits in your face up."[37] The women are surrounded by a parade of naked men riding horses, donkeys, unicorns, camels and other exotic or fantastic creatures.[28] Several men show acrobatics while riding, apparently acts designed to gain the females' attending, which highlights the allure felt between the two sexes every bit groups.[31] The 2 outer springs also contain both men and women cavorting with abandon. Effectually them, birds infest the water while winged fish crawl on land. Humans inhabit giant shells. All are surrounded by oversized fruit pods and eggshells, and both humans and animals banquet on strawberries and cherries.

Detail showing nudes within a transparent sphere, which is the fruit of a found

The impression of a life lived without consequence, or what art historian Hans Belting describes as "unspoilt and pre-moral existence", is underscored by the absence of children and old people.[38] Co-ordinate to the second and tertiary chapters of Genesis, Adam and Eve's children were born later on they were expelled from Eden. This has led some commentators, in particular Belting, to theorise that the console represents the globe if the 2 had not been driven out "among the thorns and thistles of the world". In Fraenger's view, the scene illustrates "a utopia, a garden of divine delight before the Fall, or—since Bosch could not deny the existence of the dogma of original sin—a millennial condition that would arise if, afterward expiation of Original Sin, humanity were permitted to return to Paradise and to a land of tranquil harmony embracing all Cosmos."[39]

In the loftier distance of the background, above the hybrid stone formations, four groups of people and creatures are seen in flying. On the immediate left a human male rides on a chthonic solar eagle-lion. The human carries a triple-branched tree of life on which perches a bird; according to Fraenger "a symbolic bird of decease". Fraenger believes the man is intended to represent a genius, "he is the symbol of the extinction of the duality of the sexes, which are resolved in the ether into their original land of unity".[twoscore] To their correct a knight with a dolphin tail sails on a winged fish. The knight's tail curls back to impact the back of his head, which references the mutual symbol of eternity: the snake biting its own tail. On the immediate right of the console, a winged youth soars upwards conveying a fish in his hands and a falcon on his dorsum.[forty] According to Belting, in these passages Bosch's "imagination triumphs ... the ambiguity of [his] visual syntax exceeds fifty-fifty the enigma of content, opening upward that new dimension of freedom by which painting becomes fine art."[xv] Fraenger titled his affiliate on the high background "The Ascent to Heaven", and wrote that the airborne figures were likely intended every bit a link between "what is in a higher place" and "what is below", just as the left and right hand panels represent "what was" and "what volition be".[41]

Correct console [edit]

A scene from the hellscape panel showing the long beams of calorie-free emitted from the burning city in the panel'south background[xviii]

The right panel (220 × 97.five cm, 87 × 38.4 in) illustrates Hell, the setting of a number of Bosch paintings. Bosch depicts a world in which humans have succumbed to temptations that lead to evil and reap eternal damnation. The tone of this last console strikes a harsh contrast to those preceding it. The scene is gear up at night, and the natural dazzler that adorned the earlier panels is noticeably absent. Compared to the warmth of the center panel, the correct wing possesses a chilling quality—rendered through cold colourisation and frozen waterways—and presents a tableau that has shifted from the paradise of the heart epitome to a spectacle of cruel torture and retribution.[42] In a single, densely detailed scene, the viewer is made witness to cities on fire in the background; war, torture chambers, infernal taverns, and demons in the midground; and mutated animals feeding on homo flesh in the foreground.[43] The nakedness of the human figures has lost all its eroticism, and many now attempt to embrace their genitalia and breasts with their hands, ashamed by their nakedness.[18]

Large explosions in the groundwork throw light through the city gates and spill into the water in the midground; according to writer Walter S. Gibson, "their peppery reflection turning the water below into blood".[18] The calorie-free illuminates a road filled with fleeing figures, while hordes of tormentors gear up to burn down a neighbouring hamlet.[44] A brusque distance away, a rabbit carries an impaled and bleeding corpse, while a grouping of victims above are thrown into a burning lantern.[45] The foreground is populated by a variety of distressed or tortured figures. Some are shown airsickness or excreting, others are crucified by harp and lute, in an allegory of music, thus sharpening the contrast between pleasance and torture. A choir sings from a score inscribed on a pair of buttocks,[42] part of a group that has been described every bit the "Musicians' Hell".[46]

The "Tree-Homo" of the right console, and a pair of human ears brandishing a blade. A cavity in the torso is populated by three naked persons at a table, seated on an creature, and a fully clothed woman pouring drink from a barrel.

The focal point of the scene is the "Tree-Man", whose cavernous torso is supported by what could be contorted arms or rotting tree trunks. His head supports a deejay populated past demons and victims parading around a huge set of bagpipes—ofttimes used as a dual sexual symbol[42]—reminiscent of human scrotum and penis. The tree-human's torso is formed from a broken eggshell, and the supporting trunk has thorn-like branches which pierce the fragile body. A grey effigy in a hood begetting an arrow jammed between his buttocks climbs a ladder into the tree-man'due south central cavity, where nude men sit down in a tavern-like setting. The tree-man gazes outwards across the viewer, his conspiratorial expression a mix of wistfulness and resignation.[47] Belting wondered if the tree-man's face up is a cocky-portrait, citing the figure's "expression of irony and the slightly sideways gaze [which would] so establish the signature of an creative person who claimed a bizarre pictorial globe for his own personal imagination".[42]

Many elements in the panel incorporate earlier iconographical conventions depicting hell. Yet, Bosch is innovative in that he describes hell not as a fantastical identify, but as a realistic world containing many elements from twenty-four hours-to-day human life.[43]

Gibson compares this "Prince of Hell" to a figure in the 12th-century Irish religious text Vision of Tundale, who feeds on the souls of corrupt and lecherous clergy.[47]

Animals are shown punishing humans, subjecting them to nightmarish torments that may symbolise the seven mortiferous sins, matching the torment to the sin. Sitting on an object that may be a toilet or a throne, the panel's centerpiece is a gigantic bird-headed monster feasting on human corpses, which he excretes through a cavity below him,[43] into the transparent chamber pot on which he sits.[47] The monster is sometimes referred to equally the "Prince of Hell", a proper noun derived from the cauldron he wears on his head, perhaps representing a debased crown.[43] At his anxiety, a female person has her face reflected on the buttocks of a demon. Further to the left, next to a hare-headed demon, a grouping of naked persons around a toppled gambling table are being massacred with swords and knives. Other vicious violence is shown by a knight torn downwards and eaten upward by a pack of wolves to the right of the tree-man.

During the Eye Ages, sexuality and lust were seen, by some, every bit evidence of humanity'south fall from grace. In the optics of some viewers, this sin is depicted in the left-hand console through Adam's, allegedly lustful, gaze towards Eve, and it has been proposed that the center panel was created as a alarm to the viewer to avoid a life of sinful pleasure.[48] According to this view, the punishment for such sins is shown in the right console of the triptych. In the lower right-hand corner, a man is approached past a pig wearing the veil of a nun. The squealer is shown trying to seduce the man to sign legal documents. Lust is further said to be symbolised by the gigantic musical instruments and past the choral singers in the left foreground of the panel. Musical instruments often carried erotic connotations in works of art of the menses, and lust was referred to in moralising sources equally the "music of the flesh". In that location has too been the view that Bosch's use of music here might be a rebuke against traveling minstrels, oftentimes thought of as purveyors of bawdy song and poetry.[49]

Dating and provenance [edit]

The dating of The Garden of Earthly Delights is uncertain. Ludwig von Baldass (1917) considered the painting to exist an early work past Bosch.[50] However, since De Tolnay (1937)[51] consensus among 20th-century art historians placed the piece of work in 1503–1504 or even later. Both early and late datings were based on the "archaic" treatment of space.[52] Tree-ring dating dates the oak of the panels between the years 1460 and 1466, providing an earliest date (terminus post quem) for the work.[53] Wood used for panel paintings during this flow customarily underwent a lengthy period of storage for seasoning purposes, so the age of the oak might exist expected to predate the actual date of the painting by several years. Internal bear witness, specifically the depiction of a pineapple (a "New World" fruit), suggests that the painting itself postdates Columbus' voyages to the Americas, between 1492 and 1504.[53] The dendrochronological research brought Vermet[54] to reconsider an early on dating and, consequently, to dispute the presence of any "New World" objects, stressing the presence of African ones instead.[55]

The Garden was first documented in 1517, 1 twelvemonth later on the artist'southward death, when Antonio de Beatis, a catechism from Molfetta, Italy, described the piece of work equally part of the decoration in the boondocks palace of the Counts of the House of Nassau in Brussels.[56] The palace was a high-contour location, a house often visited by heads of state and leading court figures. The prominence of the painting has led some to conclude that the work was commissioned, and not "solely ... a flying of the imagination".[57] A description of the triptych in 1605 called it the "strawberry painting", because the fruit of the strawberry tree (madroño in Castilian) features prominently in the center panel. Early on Spanish writers referred to the work equally La Lujuria ("Lust").[52]

The elite of the Burgundian Netherlands, influenced past the humanist movement, were the most likely collectors of Bosch's paintings, but there are few records of the location of his works in the years immediately following his death.[58] It is probable that the patron of the work was Engelbrecht II of Nassau, who died in 1504, or his successor Henry Three of Nassau-Breda, the governor of several of the Habsburg provinces in the Depression Countries. De Beatis wrote in his travel journal that "there are some panels on which bizarre things have been painted. They represent seas, skies, woods, meadows, and many other things, such as people itch out of a shell, others that bring forth birds, men and women, white and blacks doing all sorts of unlike activities and poses."[59] Considering the triptych was publicly displayed in the palace of the House of Nassau, it was visible to many, and Bosch's reputation and fame rapidly spread across Europe. The work's popularity can be measured past the numerous surviving copies—in oil, engraving and tapestry—commissioned by wealthy patrons, also equally past the number of forgeries in circulation subsequently his decease.[60] Most are of the central panel only and do not deviate from the original. These copies were usually painted on a much smaller scale, and they vary considerably in quality. Many were created a generation after Bosch, and some took the form of wall tapestries.[61]

The De Beatis description, only rediscovered by Steppe in the 1960s,[56] cast new light on the commissioning of a work that was previously thought—since it has no central religious image—to be an atypical altarpiece. Many Netherlandish diptychs intended for private use are known, and even a few triptychs, simply the Bosch panels are unusually large compared with these and incorporate no donor portraits. Mayhap they were commissioned to celebrate a hymeneals, as big Italian paintings for private houses ofttimes were.[62] Nonetheless, The Garden 'southward bold depictions do not dominion out a church commission, such was the contemporaneous fervor to warn confronting immorality.[52] In 1566, the triptych served as the model for a tapestry that hangs at El Escorial monastery almost Madrid.[63]

Upon the death of Henry Iii, the painting passed into the hands of his nephew William the Silent, the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau and leader of the Dutch Revolt against Spain. In 1568, still, the Duke of Alba confiscated the pic and brought information technology to Kingdom of spain,[64] where it became the property of one Don Fernando, the Duke's illegitimate son and heir and the Spanish commander in kingdom of the netherlands.[65] Philip Two caused the painting at sale in 1591; two years later he presented it to El Escorial. A contemporaneous description of the transfer records the gift on viii July 1593[52] of a "painting in oils, with two wings depicting the variety of the globe, illustrated with grotesqueries past Hieronymus Bosch, known as 'Del Madroño'".[66] After an unbroken 342 years at El Escorial, the work moved to the Museo del Prado in 1939,[67] along with other works past Bosch. The triptych was not particularly well-preserved; the pigment of the middle console peculiarly had flaked off effectually joints in the wood.[52] However, contempo restoration works have managed to recover and maintain it in a very good state of quality and preservation.[68] The painting is normally on display in a room with other works past Bosch.[69]

Sources and context [edit]

Hieronymus Bosch, Human being Tree, c. 1470s. The "Tree-Man" of the right-hand panel, depicted in an before drawing by Bosch. This pen and bistre version contains no suggestion of Hell, yet its outline was adapted into one of The Garden 's most memorable grotesques.[42]

Little is known for certain of the life of Hieronymus Bosch or of the commissions or influences that may have formed the basis for the iconography of his piece of work. His birthdate, education and patrons remain unknown. There is no surviving record of Bosch'southward thoughts or prove every bit to what attracted and inspired him to such an individual fashion of expression.[70] Through the centuries fine art historians have struggled to resolve this question however conclusions remain bitty at best. Scholars have debated Bosch'due south iconography more extensively than that of any other Netherlandish creative person.[71] His works are more often than not regarded as enigmatic, leading some to speculate that their content refers to contemporaneous esoteric knowledge since lost to history.

Hieronymus Bosch, in a c. 1550 drawing in one case idea to be a copy of a self-portrait. His age in this representation (believed to be effectually 60 years) has been used to estimate his date of birth, although its attribution remains uncertain.[72]

Although Bosch's career flourished during the High Renaissance, he lived in an surface area where the beliefs of the medieval Church building still held moral dominance.[73] He would have been familiar with some of the new forms of expression, especially those in Southern Europe, although it is difficult to attribute with certainty which artists, writers and conventions had a begetting on his work.[71] José de Sigüenza is credited with the start extensive critique of The Garden of Earthly Delights, in his 1605 History of the Lodge of St. Jerome.[74] He argued confronting dismissing the painting as either heretical or merely absurd, commenting that the panels "are a satirical comment on the shame and sinfulness of mankind".[74] The art historian Carl Justi observed that the left and middle panels are drenched in tropical and oceanic atmosphere, and concluded that Bosch was inspired by "the news of recently discovered Atlantis and by drawings of its tropical scenery, but every bit Columbus himself, when approaching terra firma, thought that the place he had plant at the oral cavity of the Orinoco was the site of the Earthly Paradise".[75] The period in which the triptych was created was a time of adventure and discovery, when tales and trophies from the New Globe sparked the imagination of poets, painters and writers.[76] Although the triptych contains many unearthly and fantastic creatures, Bosch nonetheless appealed in his images and cultural references to an aristocracy humanist and aristocratic audience. Bosch reproduces a scene from Martin Schongauer's engraving Flight into Egypt.[77]

Conquest in Africa and the Eastward provided both wonder and terror to European intellectuals, as information technology led to the conclusion that Eden could never have been an bodily geographical location. The Garden references exotic travel literature of the 15th century through the animals, including lions and a giraffe, in the left console. The giraffe has been traced to Cyriac of Ancona, a travel author known for his visits to Egypt during the 1440s. The exoticism of Cyriac'due south sumptuous manuscripts may have inspired Bosch'due south imagination.[78]

The giraffe on the right side of the left panel may be drawn from copies of those in Cyriac of Ancona's Egyptian Voyage (left), which was published c. 1440.[22]

The charting and conquest of this new world fabricated existent regions previously just idealised in the imagination of artists and poets. At the same fourth dimension, the certainty of the old biblical paradise began to slip from the grasp of thinkers into the realms of mythology. In response, treatment of the Paradise in literature, poetry and art shifted towards a cocky-consciously fictional Utopian representation, as exemplified past the writings of Thomas More (1478–1535).[79]

Albrecht Dürer was an avid student of exotic animals, and drew many sketches based on his visits to European zoos. Dürer visited 'southward-Hertogenbosch during Bosch'southward lifetime, and it is likely the two artists met, and that Bosch drew inspiration from the German's work.[lxxx]

Attempts to find sources for the work in literature from the period have not been successful. Fine art historian Erwin Panofsky wrote in 1953 that, "In spite of all the ingenious, erudite and in part extremely useful research devoted to the task of "decoding Jerome Bosch", I cannot aid feeling that the real hole-and-corner of his magnificent nightmares and daydreams has still to be disclosed. Nosotros accept bored a few holes through the door of the locked room; but somehow nosotros practice not seem to have discovered the key."[81] [82] The humanist Desiderius Erasmus has been suggested equally a possible influence; the author lived in 's-Hertogenbosch in the 1480s, and it is likely he knew Bosch. Glum remarked on the triptych's similarity of tone with Erasmus's view that theologians "explain (to conform themselves) the nigh difficult mysteries ... is it a possible suggestion: God the Father hates the Son? Could God have causeless the form of a woman, a devil, an ass, a gourd, a stone?"[83]

Estimation [edit]

Detail from the center panel showing two cherry-adorned dancing figures who bear a surface on which an owl is perched. In the front right corner a bird standing on a reclining man's foot is nearly to eat from a cherry offered to it.

Because only bare details are known of Bosch's life, interpretation of his work can be an extremely difficult area for academics as it is largely reliant on conjecture. Individual motifs and elements of symbolism may be explained, but and so far relating these to each other and to his piece of work every bit a whole has remained elusive.[17] The enigmatic scenes depicted on the panels of the inner triptych of The Garden of Earthly Delights have been studied by many scholars, who have often arrived at contradictory interpretations.[59] Analyses based on symbolic systems ranging from the alchemical, astrological, and heretical to the folkloric and hidden take all attempted to explain the complex objects and ideas presented in the piece of work.[84] Until the early 20th century, Bosch's paintings were generally thought to incorporate attitudes of Medieval didactic literature and sermons. Charles De Tolnay wrote that

The oldest writers, Dominicus Lampsonius and Karel van Mander, attached themselves to his most evident side, to the subject; their conception of Bosch, inventor of fantastic pieces of devilry and of infernal scenes, which prevails today (1937) in the public at large, and prevailed with historians until the concluding quarter of the 19th century.[85]

Generally, his work is described as a warning against lust, and the central panel equally a representation of the transience of worldly pleasure. In 1960, the art historian Ludwig von Baldass wrote that Bosch shows "how sin came into the earth through the Creation of Eve, how fleshly lusts spread over the entire world, promoting all the Deadly Sins, and how this necessarily leads straight to Hell".[86] De Tolnay wrote that the center console represents "the nightmare of humanity", where "the artist'southward purpose above all is to bear witness the evil consequences of sensual pleasure and to stress its imperceptible character".[87] Supporters of this view hold that the painting is a sequential narrative, depicting mankind's initial state of innocence in Eden, followed by the subsequent corruption of that innocence, and finally its penalization in Hell. At various times in its history, the triptych has been known equally La Lujuria, The Sins of the Earth and The Wages of Sin.[xxx]

Proponents of this idea indicate out that moralists during Bosch's era believed that it was woman's—ultimately Eve's—temptation that drew men into a life of lechery and sin. This would explain why the women in the center panel are very much amidst the active participants in bringing near the Fall. At the time, the ability of femininity was oft rendered past showing a female person surrounded by a circle of males. A late 15th-century engraving past Israhel van Meckenem shows a group of men prancing ecstatically around a female figure. The Master of the Banderoles'southward 1460 work the Pool of Youth similarly shows a group of females continuing in a space surrounded by admiring figures.[31]

This line of reasoning is consistent with interpretations of Bosch'southward other major moralising works which hold upward the folly of human; the Death and the Miser and the Haywain. Although according to the art historian Walter Bosing, each of these works is rendered in a mode that it is hard to believe "Bosch intended to condemn what he painted with such visually enchanting forms and colors". Bosing concludes that a medieval mindset was naturally suspicious of fabric dazzler, in any class, and that the sumptuousness of Bosch's description may have been intended to convey a fake paradise, teeming with transient beauty.[88]

In 1947, Wilhelm Fränger argued that the triptych'southward centre panel portrays a joyous globe when mankind will experience a rebirth of the innocence enjoyed by Adam and Eve earlier their fall.[89] In his book The Millennium of Hieronymus Bosch, Fränger wrote that Bosch was a member of the heretical sect known as the Adamites—who were as well known as the Homines intelligentia and Brethren and Sisters of the Gratuitous Spirit. This radical grouping, active in the area of the Rhine and the Netherlands, strove for a form of spirituality immune from sin even in the mankind, and imbued the concept of lust with a paradisical innocence.[90]

Fränger believed The Garden of Earthly Delights was commissioned by the order's M Primary. Later critics have agreed that, because of their obscure complexity, Bosch'due south "altarpieces" may well have been commissioned for non-devotional purposes. The Homines intelligentia cult sought to regain the innocent sexuality enjoyed by Adam and Eve before the Fall. Fränger writes that the figures in Bosch'southward work "are peacefully frolicking about the tranquil garden in vegetative innocence, at one with animals and plants and the sexuality that inspires them seems to exist pure joy, pure bliss."[91] Fränger argued confronting the notion that the hellscape shows the retribution handed down for sins committed in the center console. Fränger saw the figures in the garden every bit peaceful, naive, and innocent in expressing their sexuality, and at one with nature. In contrast, those being punished in Hell incorporate "musicians, gamblers, desecrators of judgment and penalty".[thirty]

Examining the symbolism in Bosch's art—"the freakish riddles … the irresponsible phantasmagoria of an ecstatic"—Fränger concluded that his interpretation applied to Bosch's three altarpieces simply: The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, and the Haywain Triptych. Fränger distinguished these pieces from the artist'southward other works and argued that despite their anti-cleric polemic, they were notwithstanding all altarpieces, probably commissioned for the devotional purposes of a mystery cult.[92] While commentators have Fränger'due south analysis as acute and broad in scope, they have ofttimes questioned his final conclusions. These are regarded by many scholars every bit hypothesis just, and built on an unstable foundation and what can only be conjecture. Critics argue that artists during this flow painted not for their own pleasure but for commission, while the linguistic communication and secularization of a post-Renaissance mind-set projected onto Bosch would have been alien to the tardily-Medieval painter.[93]

Fränger's thesis stimulated others to examine The Garden more closely. Writer Carl Linfert as well senses the joyfulness of the people in the heart panel, but rejects Fränger's exclamation that the painting is a "doctrinaire" piece of work espousing the "guiltless sexuality" of the Adamite sect.[94] While the figures engage in amorous acts without any proposition of the forbidden, Linfert points to the elements in the center panel suggesting death and temporality: some figures turn away from the action, seeming to lose promise in deriving pleasure from the passionate frolicking of their cohorts. Writing in 1969, E. H. Gombrich drew on a close reading of Genesis and the Gospel According to Saint Matthew to advise that the fundamental panel is, according to Linfert, "the country of mankind on the eve of the Alluvion, when men still pursued pleasure with no idea of the morrow, their only sin the unawareness of sin."[94]

Legacy [edit]

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Dull Gret, 1562. While Bruegel's Hellscapes were influenced by The Garden 'south right panel, his aesthetic betrays a more pessimistic view of humanity's fate.

Because Bosch was such a unique and visionary creative person, his influence has not spread as widely every bit that of other major painters of his era. However, in that location take been instances of later artists incorporating elements of The Garden of Earthly Delights into their ain work. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569) in item directly acknowledged Bosch as an important influence and inspiration,[96] [97] and incorporated many elements of the inner correct console into several of his nigh popular works. Bruegel'due south Mad 1000000 depicts a peasant woman leading an army of women to pillage Hell, while his The Triumph of Death (c. 1562) echoes the monstrous Hellscape of The Garden, and utilizes, according to the Imperial Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, the same "unbridled imagination and the fascinating colours".[98]

While the Italian court painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (c. 1527–1593) did not create Hellscapes, he painted a body of strange and "fantastic" vegetable portraits—generally heads of people composed of plants, roots, webs and various other organic thing. These strange portraits rely on and echo a motif that was in part inspired past Bosch's willingness to break from strict and true-blue representations of nature.[99]

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Winter, 1573. The concept of the "Tree-man", the hybrid organism, as well the engorged fruit, all comport hallmarks of Bosch's Garden.

David Teniers the Younger (c. 1610–1690) was a Flemish painter who quoted both Bosch and Bruegel throughout his career in such works as his versions of the Temptation of St Anthony, the Rich Human being in Hell and his version of Mad 1000000.

During the early 20th century, Bosch'southward work enjoyed a popular resurrection. The early surrealists' fascination with dreamscapes, the autonomy of the imagination, and a costless-flowing connection to the unconscious brought about a renewed interest in his piece of work. Bosch'due south imagery struck a chord with Joan Miró[100] and Salvador Dalí[101] in particular. Both knew his paintings immediate, having seen The Garden of Earthly Delights in the Museo del Prado, and both regarded him every bit an fine art-historical mentor. Miró's The Tilled Field contains several parallels to Bosch's Garden: similar flocks of birds; pools from which living creatures sally; and oversize disembodied ears all echo the Dutch master's piece of work.[100] Dalí's 1929 The Bang-up Masturbator is similar to an image on the right side of the left panel of Bosch's Garden, composed of rocks, bushes and little animals resembling a face with a prominent nose and long eyelashes.[102]

When André Breton wrote his first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, his historical precedents every bit inclusions named only Gustave Moreau, Georges Seurat, and Uccello. However, the Surrealist motion soon rediscovered Bosch and Bruegel, who quickly became popular amid the Surrealist painters. René Magritte and Max Ernst[103] both were inspired by Bosch'southward The Garden of Earthly Delights.

In the 2004 Shine moving picture The Garden of Earthly Delights (Ogród rozkoszy ziemskich), ii lovers recreate some of the figures from the Bosch painting equally tableau vivant performances in celebration of life after the woman finds that she is dying.[104]

Notes [edit]

- ^ At the time, paintings oftentimes had no fixed titles. It is listed in Philip IV of Spain's inventory equally La Pintura del Madroño. It is known today in Spanish, at the Prado Museum, equally El Jardín de las Delicias.

Citations [edit]

- ^ Bosch's exact engagement of birth is unknown only is estimated to exist 1450. Gibson, 15–xvi

- ^ Belting, 85–86

- ^ Gibson, 99

- ^ a b c von Baldass, 33

- ^ a b Snyder 1977, 102

- ^ a b c Belting, 21

- ^ Veen & Ridderbos, 6

- ^ The drenched state of the Globe has led some to translate the panels as depicting The Inundation. In Mann, 2005

- ^ Belting, 22

- ^ Gibson, 88

- ^ Dempsey, Charles. "Sicut in utrem aquas maris: Jerome Bosch's Prolegomenon to the Garden of Earthly Delights". MLN. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 119:1, January 2004. S247–S270. Retrieved Nov 14, 2007

- ^ Cinotti, 100

- ^ a b Calas, Elena. "D for Deus and Diabolus. The Iconography of Hieronymus Bosch". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Volume 27, No. 4, Summer, 1969. 445–454

- ^ Glum, 45

- ^ a b c Belting, 57

- ^ Gibson, 91

- ^ a b c Dixon, Laurinda S. "Bosch'south Garden of Delights: Remnants of a 'Fossil' Science". Art Bulletin, LXIII, 1981. 96–113

- ^ a b c d Gibson, 92

- ^ Fraenger, 44

- ^ a b Gibson, 25

- ^ Fraenger, 46

- ^ a b c Belting, 26

- ^ a b Tuttle, Virginia. "Lilith in Bosch's 'Garden of Earthly Delights'". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Fine art, Book 15, No. 2, 1985. 119

- ^ Gibson, 92–93

- ^ Fraenger, 122

- ^ Linfert, 106–108

- ^ Mann, Richard M. "Melanie Klier's: Hieronymus Bosch: Garden of Earthly Delights". Utopian Studies, 16.1, 2005

- ^ a b Belting, 47

- ^ Gibson, 80

- ^ a b c Fraenger, 10

- ^ a b c d Gibson, 85

- ^ Reuterswärd, Patrik. "A New Inkling to Bosch's Garden of Delights". The Art Bulletin, Book 64, No. 4, December 1982. 636–638: 637

- ^ Glum 2007, 253–256

- ^ a b Fraenger, 139

- ^ a b Reuterswärd, 636

- ^ Belting, 48–54

- ^ Glum, 51

- ^ Belting, 54

- ^ Fraenger, eleven

- ^ a b Fraenger, 135

- ^ Fraenger, 136

- ^ a b c d e Belting, 38

- ^ a b c d Belting, 35

- ^ Belting, 44

- ^ Gibson, 96

- ^ Harbison, 79

- ^ a b c Gibson, 97–98

- ^ Gibson, 82

- ^ a b Bosing, lx

- ^ Baldass, Ludwig von, "Die Chronologie der Gemälde des Hieronymus Bosch", in: Jahrbuch der königlichen Preuszischen Kunstsammlungen, XXXVIII (1917), pp. 177–195

- ^ Tolnay, Charles de Hieronymus Bosch. Basel, 1937

- ^ a b c d due east Cinotti, 99

- ^ a b Glum 2007, three

- ^ Vermet, Bernard M.. "Hieronymus Bosch: painter, workshop or fashion?" in Koldeweij et al. 2001a, 84–99:90–91. Extended argumentation in: Vermet, Bernard M.."Baldass was right" in Jheronimus Bosch. His Sources. second International Jheronimus Bosch Conference May 22–25, 2007 Jheronimus Bosch Art Center. 's-Hertogenbosch 2010. ISBN 978-ninety-816227-iv-5 "Online".

- ^ Vermet 2010

- ^ a b This fact was merely discovered by J. K. Steppe in 1962 (Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie voor Wegenschaften 24 [1962], 166–167), 20 years after Fraenger speculated the triptych was commissioned past the yard primary of a heretical sect, but five years earlier E. H. Gombrich claimed to have discovered the Nassau provenance. In Belting, 71

- ^ Belting, 71

- ^ Moxey, 107–108. Works commissioned and owned by churches or royalty are more than likely to have surviving documentation

- ^ a b Silver, Larry. "Hieronymus Bosch, Tempter and Moralist". Per Contra: The International Journal of the Arts, Literature and Ideas, Winter 2006–2007. Retrieved April 27, 2008

- ^ "Bosch and Bruegel: Inventions, Enigmas and Variations Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine ". The National Gallery, London. Printing release annal, Nov 2003. Retrieved May 26, 2008

- ^ Belting, 79–81

- ^ Harbison, 77–eighty

- ^ Snyder 1977, 96

- ^ Belting, 78

- ^ Vandenbroeck, Paul. "High stakes in Brussels, 1567. The Garden of Earthly Delights as the crux of the conflict between William the Silent and the Duke of Alva", in Koldeweij, et al. 2001b, 87–90

- ^ Larsen, 26

- ^ Prado, 36

- ^ "La restauración del Jardín de las delicias - Voz - Museo Nacional del Prado".

- ^ "New Bosch display at the Prado". Art History News. November 2020.

- ^ Fraenger, one

- ^ a b Snyder 2004, 395–396

- ^ Gibson, 16

- ^ Gibson, xiv

- ^ a b Gómez, 22

- ^ Fraenger, 57

- ^ Gibson, 27

- ^ Gibson, 26

- ^ Vandenbroeck, Paul. "The Spanish inventarios reales and Hieronymus Bosch", in Koldeweij et al., 49–63:59–threescore

- ^ Belting, 98–99

- ^ Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. "Netherlandish Artists and Art in Renaissance Nuremberg". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, Volume xx, Number two/three, 1990–1991. 153–167

- ^ Quoted in Moxey, 104.

- ^ Bosch was christened Jeroen van Aken but took surname Bosch from the town he lived in for most of his life. Hieronymus is the Latin course of Jerome. In Rooth, 12. ISBN 951-41-0673-3

- ^ Glum, 49

- ^ Gombrich, Due east. H. "Bosch's 'Garden of Earthly Delights': A Progress Report". Periodical of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Volume 32, 1969: 162–170

- ^ Grange Books, 23

- ^ von Baldass, 84

- ^ Glum, 1976

- ^ Bosing, 56

- ^ Snyder 1977, 100

- ^ Grange books, 37

- ^ Bosing, 51.

- ^ Grange Books, 32

- ^ Grange Books, 38

- ^ a b Linfert, 112

- ^ Spector, Nancy. "The Tilled Field, 1923–1924 Archived 2008-09-25 at the Wayback Motorcar". Guggenheim display caption. Retrieved May thirty, 2008

- ^ Burness, Donald B. "Pieter Bruegel: Painter for Poets". Fine art Journal, Volume 32, No. 2, Winter, 1972–1973. 157–162

- ^ Jones, Jonathan. "The end of innocents". The Guardian, January 17, 2004. Retrieved May 27, 2008

- ^ "Mad Million by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1561–62". Regal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp. Retrieved May 27, 2008

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael. "Arcimboldo's Feast for the Optics". The New York Times, October ten, 2007. Retrieved May 27, 2008

- ^ a b Moray, Gerta. "Miró, Bosch and Fantasy Painting". The Burlington Magazine, Volume 113, No. 820, July 1971. 387–391

- ^ Fanés, Fèlix. Salvador Dalí: The Construction of the Paradigm, 1925–1930. Yale University Printing, March, 2007. 121. ISBN 0-300-09179-6

- ^ Félix Fanès: Salvador Dalí. The Construction of the Image 1925–1930. Yale University Press 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-09179-three, p. 74

- ^ Moray, Gerta. "Miró, Bosch and Fantasy Painting". The Burlington Magazine, Volume 113, No. 820, July 1971. Max Ernst'south favourite painters and poets of the past, p. 387

- ^ Ágnes, Pethő (2015), ""Housing" a Deleuzian "Sensation:" Notes on the Post-Cinematic Tableaux Vivants of Lech Majewski, Sharunas Bartas and Ihor Podolchak", in Pethő, Ágnes (ed.), The Picture palace of Sensations, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 155, 157–158, ISBN978-1-4438-6883-9

Sources [edit]

- Baldass, Ludwig von. Hieronymus Bosch. London: Thames and Hudson, 1960. ASIN B0007DNZR0

- Belting, Hans. Garden of Earthly Delights. Munich: Prestel, 2005. ISBN 3-7913-3320-viii.

- Bosing, Walter. Hieronymus Bosch, C. 1450–1516: Between Heaven and Hell. Berlin: Taschen, 2000. ISBN 3-8228-5856-0.

- Boulboullé, Guido, "Groteske Malaise. Die Höllenphantasien des Hieronymus Bosch". In: Auffarth, Christoph and Kerth, Sonja (Eds): "Glaubensstreit und Gelächter: Reformation und Lachkultur im Mittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit", LIT Verlag Berlin, 2008, pp. 55–78.

- Cinotti, Mia. The Complete Paintings of Bosch. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969.

- De Beatis, Antonio. The Travel Journal of Antonio De Beatis Through Germany, Switzerland, the Depression Countries, France and Italy, 1517–xviii. London: Hakluyt Order, 1999. ISBN 0-904180-07-vii.

- De Tolnay, Charles. Hieronymus Bosch. Tokyo: Eyre Methuen, 1975. ISBN 0-413-33280-ii. Original publication: Hieronymus Bosch, Basel: Holbein, 1937, 129 pages text, 128 pages images.

- Delevoy, Robert L. Bosch: Biographical and Critical Study. Lausanne: Skira, 1960.

- Fraenger, Wilhelm and Kaiser, Ernst. The Millennium of Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Hacker Fine art Books, 1951. Original publication: Wilhelm Fraenger, Hieronymus Bosch – das Tausendjährige Reich. Grundzüge einer Auslegung, Winkler-Verlag Coburg 1947, 142 pages[ ISBN missing ]

- Gibson, Walter S. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1973. ISBN 0-500-20134-Ten.

- Glum, Peter. "Divine Judgment in Bosch's 'Garden of Earthly Delights". The Art Bulletin, Volume 58, No. 1, March 1976, 45–54.

- Glum, Peter. The key to Bosch'south "Garden of Earthly Delights" found in allegorical Bible interpretation, Volume I. Tokyo: Chio-koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2007. ISBN 978-four-8055-0545-eight.

- Gómez, Isabel Mateo. "Hieronymus Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights". In Gaillard, J. and M. Hieronymus Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights. New York: Clarkson Due north. Potter, 1989. ISBN 0-517-57230-iii.

- Harbison, Craig. The Art of the Northern Renaissance. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995. ISBN 0-297-83512-two.

- Kleiner, Fred & Mamiya, Christian J. Gardner'southward Art Through the Ages. California: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning, 2005. ISBN 0-534-64091-five.

- Koldeweij, A. Grand. (Jos) and Vandenbroeck, Paul and Vermet, Bernard G. Hieronymus Bosch: The Consummate Paintings and Drawings. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001(a). ISBN 0-8109-6735-9.

- Koldeweij, A. K. (Jos) and Vermet, Bernard M. with Kooy, Barbera van (edit.) Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights Into His Life and Piece of work. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001(b). ISBN 90-5662-214-5.

- Larsen, Erik. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Smithmark, 1998. ISBN 0-7651-0865-viii.

- Linfert, Carl (tr. Robert Erich Wolf). Bosch. London: Thames and Hudson, 1972. ISBN 0-500-09077-7. Original publication: Hieronymus Bosch – Gesamtausgabe der Gemälde, Köln: Phaidon Verlag 1959, 26 pages text, 93 pages images.

- Moxey, Keith. "Hieronymus Bosch and the 'World Upside Down': The Case of The Garden of Earthly Delights". Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Printing, 1994, 104–140. ISBN 0-8195-6267-X.

- Oliveira, Paulo Martins, Jheronimus Bosch, 2012, ISBN 978-ane-4791-6765-iv.

- Pokorny, Erwin, "Hieronymus Bosch und das Paradies der Wollust". In: "Frühneuzeit-Info", Jg. 21, Heft 1+2 (Sonderband "Die Sieben Todsünden in der Frühen Neuzeit"), 2010, pp. 22–34.

- Rooth, Anna Birgitta. Exploring the garden of delights: Essays in Bosch'due south paintings and the medieval mental civilization. California: Suomalainen tiedeakatemia, 1992. ISBN 951-41-0673-three.

- Snyder, James. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Excalibur Books, 1977. ISBN 0-89673-060-3.

- Snyder, James. The Northern Renaissance: Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350 to 1575. Second edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2004. ISBN 0-xiii-150547-five.

- Veen, Henk Van & Ridderbos, Bernhard. Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception, and Research. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004. ISBN 90-5356-614-7.

- Vermet, Bernard M. "Baldass was right" in Jheronimus Bosch. His Sources. 2nd International Jheronimus Bosch Conference May 22–25, 2007 Jheronimus Bosch Fine art Center. 's-Hertogenbosch 2010. ISBN 978-90-816227-4-5 "Online".

- Hieronymus Bosch. London: Grange Books, 2005. ISBN 1-84013-657-X.

- Matthijs Ilsink, Jos Koldeweij, Hieronymus Bosch: Painter and Draughtsman – Catalogue raisonné, Mercatorfonds nv; 2016.

External links [edit]

- At the Museo Nacional del Prado

- "Bosch painted Garden of Earthly Delights for Brussels Palace" Audiovisual by Tvbrussel, 2016

- "The Garden of Earthly Delights: A diachronic interpretation of Hieronymus Bosch's masterpiece" A lecture by Matthias Riedl

- Audiovisual tour of The Garden of Earthly Delights narrated by Redmond O'Hanlon

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Waldemar Januszczak: Art Detective Podcast, 25 Jan 2017

- Panorama of the painting

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Garden_of_Earthly_Delights

0 Response to "Church Art Bird Carrying Body Through the Clouds to Heaven"

Post a Comment